Debunking "How to Argue with a Racist" by Adam Rutherford, Part I

Rutherford is a dishonest activist and his book is terrible

Adam Rutherford’s book “How to Argue with a Racist” is marketed as a “weapon” against “scientific racism.” One reviewer describes it as “the perfect ammunition to respond to racial discrimination should you encounter someone trying to justify their prejudice with science.” Obviously, it is an example of activist literature, not honest inquiry. Because of this, I debated even bothering to respond. Rutherford and activists like him don’t deserve anyone’s attention. Nevertheless, somebody has to clean up his mess. I think of high potential, red-pillable 15 year olds, how that was me some years back, and how if I had lived in the total information control regime of 1990 or if amazing individuals like Ryan Faulk had never made content like this debunking Patriciate propaganda in a way that is accessible to uneducated, intelligent individuals who don’t yet know there is a problem, I would have never have woken up and could still be some cringe libertarian or normie-con.

For a weapon against “racism”, Rutherford’s book isn’t very sharp. It’s written in that obnoxious New York Times best-seller style — the one where the science is never too dense, lest the author loses money because a decent chunk of the population doesn’t have the functional literacy to read such a text (the average person misses every other question on the reading SAT, so best-seller prose is obviously going to be on a 6th grade level). This indicates that the book, in addition to being blatantly motivated by activism, is also more of a commodity than a work of science. Adding to its style issues are the fact that he doesn’t cite his sources. How did this become acceptable in the mainstream press? Proper citation shouldn’t interfere with the ability of a 100 IQ person to understand a book. It’s yet another indication that this book is a hack-job written by an incompetent, greedy activist, and not a serious scholar. Contrast his book with mine, which features proper citation and dense prose, because I wasn’t about to downgrade an important scientific work for the masses.

Rutherford’s book has four parts. We will deal with each part in their own sections in separate posts.

Against Part One: “Skin in the Game”

Part one begins by using the rhetorical tactic known as mystification to attempt to convince the reader that, at worst (from Rutherford’s perspective), the evidence is unclear or inconclusive at to whether or not race is real or “scientific racism” is correct.

For example:

The picture of genetic inheritance turned out to be much more complicated in humans than in peas. Our old simplistic models of how a specific gene relates to a particular characteristic have been eroded in the last couple of decades. This is not news in relation to complex human traits, such as intelligence or diseases such as schizophrenia, where dozens or sometimes hundreds of genes have been revealed to play a small but cumulative role in their development. We’ve known this for some years. Genomes are complex and dynamic ecosystems, in which genes have multiple jobs in the body, depending on where and when they are required. A gene involved in the growth of an embryo just after conception might have a very different role later in life, or no role whatsoever. A gene may have multiple roles – an effect we call pleiotropy. Another phenomenon, known as epistasis, means that the impact of one gene is dependent on others; its effect can be positive or negative and can occur between completely different genes in networks, or even between the two copies of each gene that we all have, one set inherited from each parent. Genes do many things in many ways, and even over a lifetime of studying them, you will still find new ways the human genome works. The genetic code has remained static for billions of years, but evolution has incessantly tinkered with how it is used to build a life. (p. 25)

Nothing here is wrong, per se — I’m sure Rutherford would recognize that the Mendelian model works for sickle cell anemia, and not for height or IQ — but the general vibe promotes a feeling of the subversion or “erosion” of the racist old models of the past. The reader is supposed to be primed to think that someone like me is just an outdated Mendelian. The genome is simply too complex and dynamic — too vast and interweaved a tapestry — for something like “black people” to exist.

This is somewhat intelligent on Rutherford’s part — he is attempting to ensure, right off the bat, that if a reader is exposed to a debunking like this, their reaction will be to say, “well, of course Rutherford might have been wrong about some things, or might have left some things out, but that’s expected, because he admitted on the first page that this stuff is really dynamic and complex, and on that basis I find this racist’s certainty unconvincing.” As an expert, I can say with certainty that both his claims about race and his meta-level hand-waving about “complexity” are incorrect. We will see this clearly from the evidence, but for now, think about which side in a debate would be more likely to engage in mystification — activist liars or truth-seekers? If the evidence were clearly on the side of environmentalists, one would expect “scientific racists” to mystify, deconstruct, and make isolated demands for rigor, since their position would be made untenable by the evidence otherwise. The side which truth disfavors is more likely to mystify.

Just know that when Rutherford calls polygenic traits “inscrutably complex”:

That was textbook until December 2018, when a large genetic survey revealed that the ginger variants in MC1R account for around 70 per cent of ginger-haired people, and that the majority of people with two supposedly ginger variants in fact have brown or blonde hair. Almost 200 genes appear to have some influence over pigmentation in hair, which is about 1 per cent of the total number of genes in the human genome. It is only in the era of huge genomic datasets that this type of result could be exposed: the scientists responsible for the study looked at 350,000 people to reveal that the once-simple model of ginger hair is much closer to being inscrutably complex. (p. 26)

That this is only for him, probably due to a poor grasp on mathematics, if he’s not just being a totally cynical tactical mystifier. Yes, models for polygenic traits are more complicated than models for Mendelian traits. No, they are not “inscrutable” for people in the top percentile of intelligence. With proper statistical models, we should be able to predict hair color with basically total accuracy given a small tolerance threshold for miniscule environmental variation from a DNA sample. Neural networks are, with theoretical certainty, capable of achieving this, so long as we can train them properly on good enough data. If Rutherford is under 120 IQ, however, I could understand if he finds the math implicit in the last two sentences to be inscrutably complex compared to Punnett squares.

After beginning with mystification, Rutherford switches into race denial.

It is wholly unsurprising that, with a population of over 1.2 billion in fifty-four countries, the skin colour of the peoples of the African continent is a vast tapestry, which overlaps with Indians and aboriginal Australians, South Americans and some Europeans. Yet we talk about ‘black people’ or ‘brown people’. The pigmentation of a pale-skinned redheaded Scot is a long way on a colour chart from that of a typical Spaniard, though we call both of them white. The skin colour of more than a billion East Asians is similarly variable, yet nowadays, we tend not to refer to them by skin colour at all. Yellow, though an integral part of the description of East Asians for several centuries during the development of scientific racism, has fallen out of usage and is now generally accepted as being entirely inaccurate and simply racist. Instead, the main racial signifiers for East Asians are the epicanthic fold of the upper eyelid (which is also present in Berbers, the Inuit, Finns, Scandinavians, Poles, Indigenous Americans and people with Downs syndrome), and thick, straight black hair. Traditional racial categories are not consistent in their taxonomic boundaries. (p. 27)

Equating skin color with race is a classic race-denialist straw-man. Obviously, “black people” is basically an American colloquial term for “African-Americans,” who mostly have brown skin similar in tone to a lot of Latinos, Indians, and others, due to European admixture, while many continental Africans have much darker skin.

Rutherford gaslights us into saying “yellow is entirely inaccurate” as way to refer to east Asians. A quick Google search reveals this to be not true:

Apparently our ancestors were totally dishonest. Why would they ever refer to Asians as “yellow people?” Of course many Asians in the same ethnic groups are tan or white-skinned, because there’s variation in skin-color genes, just like among Europeans and every other ethnic group. The point is that the presence of yellow-ish phenotypes rightfully stuck out to European travelers, just as the extremely dark phenotypes of “black” Africans stuck out, so these races came to be called “yellow” and “black” colloquially out of basic honesty and genuine observation.

Race is not skin color. Race is deeper than that. Many races have brown skin. Multiple have white skin — Japanese, for instance, are tan to white, like southern Europeans. This is a Brahmin Indian:

Reducing race to skin color is a strawman often used by activists because it is so easy to knock down.

What is race?

Rutherford’s book at this point basically consists of inappropriate mystification and obfuscation about what race is. This makes sense; think about it: say you are wrong about something and you want to argue your wrong view. You have two options, roughly speaking: 1) make falsifiable claims, i.e. lie by commission or 2) leave out important facts, i.e. lie by omission. If you lie by commission, you can get BTFO in reviews more easily because somebody can quote you and correct you. If you lie by omission, you’re harder to quote, because you never have to say anything wrong. Instead, you simply paint a mistier picture than needed and portray the opposition as rushing to their conclusions. In this case, the best thing for the opposition to do is just lay out the part that you ignored.

Rutherford ignores the reality of race, lying by omission. He says:

So here is the baseline: all humans share almost all of their DNA, a fact that betrays our recent origins from Africa. The genetic differences between us, small though they are, account for much, but not all, of the physical variation we see or can assess. The diaspora from Africa around 70,000 years ago and continual migration and mixing since, means that we can see that there is structure within the genomes that underlies our basic biology. Very broadly, that structure corresponds with land masses, but within those groups there is huge variation, and at the edges and within these groups, there is continuity of variation. Of all the attempts over the centuries to place humans in distinct races, none succeeds. Genetics refuses to comply with these artificial and superficial categories. Skin colour, while being the most obvious difference between people, is a very bad proxy for the total amount of similarity or difference between individuals and between populations. Racial differences are skin deep. (p. 39)

Racial differences are not skin deep. Racial differences are genetically deep and, contrary to his statement “Traditional racial categories are not consistent in their taxonomic boundaries” (p. 27), traditional racial categories and stereotypes ARE consistent with the scientific, statistical view of race.

The statistical view

There are statistical methods for representing high dimension data in low dimensions. This way, we can visualize high dimensional data, detecting clusters intuitively. Principal component analysis is an example of a method used to do this.

To see this intuitively, we can go from two dimensions to one.

Above, the real data is two dimensional, because each data point consists of two values, [x1, x2]. PCA discovers that most of the variation of this data is in the [1,1] direction, and it projects the two dimensional data onto roughly that line. Imagine if it were projected onto the line [-1,1] — most of the variation would disappear. If the data pointed in a direction like [1,5], projecting onto the first dimension would lose most of the variation. PCA finds the best way to project the data into the lower dimension.

We can also go from a higher dimension down to two dimensions.

Here it finds the two vectors which explain the most variation and projects the data onto a plane computed from those vectors. You can see that if the orthogonal plane were used, you would again lose most of the variation. We can extend this to 3-million dimension data and project it onto one, two, or three dimensions in order to see important clusters, if there are any. Any clusters that appear will only represent part of the variation as well — in reality PCA shows the minimum degree to which the clusters differ, because we lose dimensions of variation in the process.

But we don’t need to rely on intuition alone to identify clusters. We can also use clustering algorithms, like k-means clustering, to identify clusters in high dimensional data for us. Data represented in PCA can then be marked with what cluster it was assigned to in the high dimension.

This is the background needed in order to understand race. Rutherford didn’t explain any of this in his whole book, and didn’t show any of the results I’m about to show. He mentions clustering studies in two paragraphs, doesn’t show the data, doesn’t explain results, and handwaves it away because “The data also showed long, clear gradients between all of the clusters, and no unambiguous way to say where one cluster ends and another begins” (p. 37). That sounds pretty vague, doesn’t it? Perhaps he doesn’t want you to examine the evidence on your own. There’s no other reason why he wouldn’t show the data. My first book is full of charts and figures adapted from studies, because I was hiding nothing.

I am better than “Dr. Rutherford.” In this not-book, I have attempted to explain PCA and clustering algorithms to you. And now, unlike him, I will actually show you the data.

This is from Guo et. al (2014). They took thousands of DNA samples from people, and used a clustering algorithm to find the clusters. Those labels are the non-black points. They overlapped more than 99% of the time with self-reported race, and are labeled as such. The genomes, which were treated as high-dimension vectors, are represented here in two dimensions via PCA. You can see a lot of variation, but not all of it. In addition, whole genomes were not used — only some parts of the genome were used, which reduces variation. You can see that Europeans share genetic borders with central Asians and Middle Easterners, which makes sense because they are classically considered caucasoids. Europeans are not confusable with non-Indian Asians (Mongoloids) or Africans (Negroids), however. Still, though Europeans share genetic borders with central Asians and Middle Easterners, they don’t have a lot of overlap — as one would expect from geography and observation. On literal, physical borders, there might be some inter-breeding, but it isn’t enough that Arabs turn white. The black dots reveal this — they are the mappings of new people onto genetic clusters. They are also put into the right cluster 99% of the time. In other words, you can spit on a computer and it can tell you your race with 99% accuracy. That is the opposite of “The data also showed long, clear gradients between all of the clusters, and no unambiguous way to say where one cluster ends and another begins” and “traditional racial categories are not consistent in their taxonomic boundaries.” Our traditional categories literally capture 99% of the possible variance able to be captured with such few labels. It’s no wonder why Rutherford doesn’t include any data like this in his book.

Race is more than skin deep

What we just showed is that when you see someone and think, “that person is black”, you know with greater than 99% accuracy that they belong to the pink cluster in the data above. This cluster is nothing but a variational cluster. It shows that people in the cluster are more similar to each other on a wide variety of genes than would be expected if they were chosen at random. When you see that somebody “is black”, you know with 99% accuracy that they belong to that cluster. When you know that they belong to that cluster, you know that there is an 80% chance that person is lactose intolerant. When you see that somebody is “white”, you know with 99% certainty that they belong to the white cluster, and that there is only a 20% chance they are lactose intolerant. Your eyes aren’t lying.

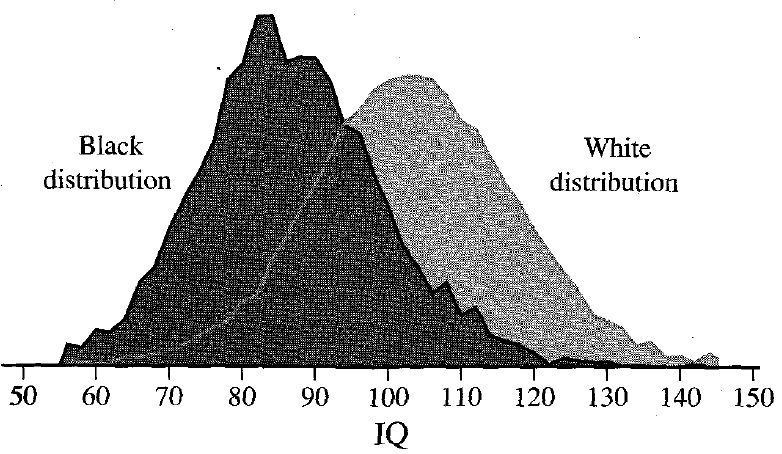

The expected value of their IQs significantly differ.

Above, EDU3 represents a sum of SNPs associated with intelligence, discovered via GWAS. It correlates with population IQ at r = 0.89. This was found in 2019, why didn’t Rutherford put this figure in his 2020 book? It seems like he can only consider a subset of the data, like any omissionist liar.

Great article, love to see jooish pseuds get BTFO

Rutherford is over lmao!