A blogger going by the name of “Inquisitive Bird” recently wrote an article titled Where Parents Make A Difference. The central thesis is basically that parenting matters, but less than genes:

Stuart Ritchie says “Parenting does matter, but it doesn’t matter as much as you think.” I wholeheartedly agree. Parents matter and they make a difference, even if the difference they make is far from as decisive as old-school sociologists thought (and some incorrectly maintain to this day). Yes, the adage that both nature and nurture matter is boring. It is also true.

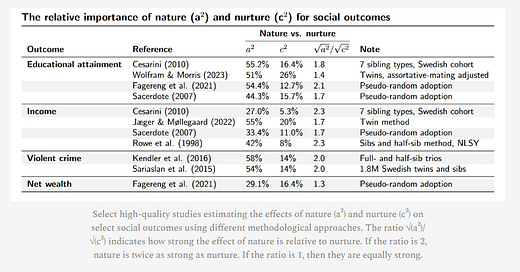

A table is provided summarizing the research cited in the blog post:

This research is all OK. I checked over it for using little kids and it seems it’s mostly all adults, so the Wilson effect is not an issue here. However, I think when one looks at the traits displayed in this table, it becomes clear that Bird is strawmanning Robert Plomin in order to make a social point. Bird says of Plomin:

For example, in his book Blueprint, the behavior geneticist Robert Plomin has a section called “Parents matter, but they don’t make a difference.” On Twitter/X I see similar claims with some regularity. Is this true? No, I will argue, the behavior genetics literature does not support this position either.

Plomin says this in connection with “physical traits”, including IQ, while Bird chooses to focus on social outcomes instead of physical traits. Here we come to a central distinction that Bird’s post obscures:

Social Outcomes vs. Physical Traits

We can obviously draw a distinction between traits like testosterone level, IQ, eye color, height, and foot size, and traits like criminal convictions, educational attainment, wealth, and income. Intuitively, some traits are going to be conceptualized as more heritable than others. When generalizing from a set of traits, it’s important to not conflate social outcome traits that are a priori likely to be lower heritability with physical traits that are not going to be changed by parental influence and friend groups.

Obviously, being adopted out to criminals can make someone more likely to go into criminal behavior, even if latent physical criminality (neurological aggression, IQ) is controlled for. The same goes for education; with IQ and conscientiousness held constant, parents and friends can still clearly influence people to invest more in education, getting one diploma more than they otherwise would have if they were adopted out to blue collar workers. On the other hand, friends will not make you grow taller, nor will they make your neurons more efficient.

Plomin was mainly talking about IQ, which I would call a physical trait. Bird only discusses social outcomes. Bird commits a category error by generalizing from social outcome environmentality to physical trait environmentalities. In fact, it’s amazing that even in social outcomes, heritability is still the main variance component.

IQ and Social Conservatism are “Physical Traits'“

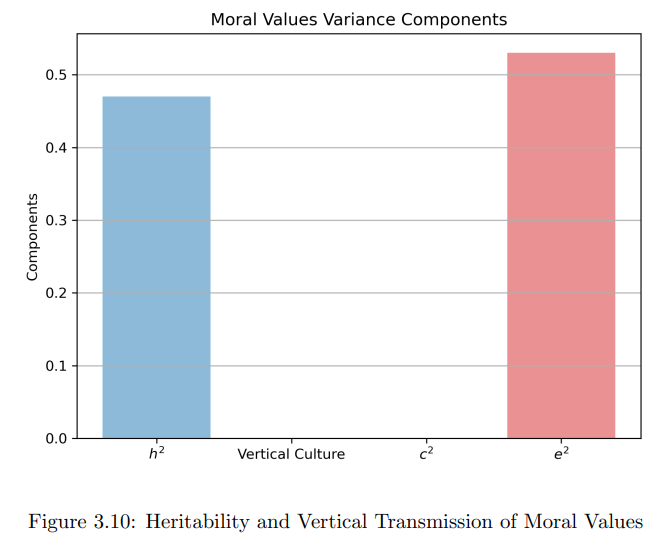

From my forthcoming book, I have charts on the variance components of social conservatism. It’s basically all genetics and nonshared environment across studies. It’s mostly genetics.

So, parents are not really influencing their child’s politics and morality through shared environment. Rather, their only influence is biological. Politics is not nurture at all, only nature, and maybe nonshared-environment information transmission.

It’s much the same for IQ scores. Parents basically do not influence IQ scores at all except through genes. This is mainly what Plomin was referring to.

Birth Order Effects

I have one other critique of Bird’s article. Bird is apparently not aware of mutational load theory, because Bird says

Another indication that nurture matters in the context of educational attainment is a highly replicated birth order effect, with earlier-born siblings nontrivially outperforming later-borns (Black et al., 2005; French et al., 2023). Isungset et al. (2022) provide some compelling evidence that the birth order effect arises out of the postnatal environment. …

Like educational attainment, birth order also affects earnings (Black et al., 2005, Table IX; Daysal et al., 2023). …

Birth order also appears to affect crime (Breining et al., 2020). …

Further, a variety of other clever designs support it (e.g., the regression discontinuity design showing that parental major affects offspring major), and so does evidence from birth order effects.

Bird reasons, in line with Insungset et al. (2022), which Bird calls “compelling”, that birth order effects sibling outcomes, yet full siblings have the same expected genetics, therefore birth order effects are due to the shared environment differing between older and younger siblings.

Isungset et al. says this:

Siblings share many environments and much of their genetics. Yet, siblings turn out different. Intelligence and education are influenced by birth order, with earlier-born siblings outperforming later-borns. We investigate whether birth order differences in education are caused by biological differences present at birth, that is, genetic differences or in utero differences. Using family data that spans two generations, combining registry, survey, and genotype information, this study is based on the Norwegian Mother, Father, and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). We show that there are no genetic differences by birth order as captured by polygenic scores (PGSs) for educational attainment. Earlier-born have lower birth weight than later-born, indicating worse uterine environments. Educational outcomes are still higher for earlier-born children when we adjust for PGSs and in utero variables, indicating that birth order differences arise postnatally. Finally, we consider potential environmental influences, such as differences according to maternal age, parental educational attainment, and sibling genetic nurture. We show that birth order differences are not biological in origin, but pinning down their specific causes remains elusive.

So, they have no direct evidence for shared environment differing between siblings. Indeed, it is counter-intuitive that it would; shared environment should stay the same for all siblings belonging to the same parents. The null hypothesis is that parents do not magically change their influence strategy, telling their younger children to not pursue school. This would be very strange. And indeed, no direct evidence has been found for this. Yet Bird calls this study “compelling evidence.”

This is not really compelling on its face, since it’s not direct. It’s merely circumstantial evidence, so I object to Bird just calling it “compelling” while not explaining the flaws in the study. It feels like a very bad citation practice, trumping up a study that supports your stuff while not discussing any of its flaws, falsely calling it “compelling” or “brilliant” when it’s not. Many people do this; economists often call the latest 2SLS paste a “brilliant exploitation of natural experimentation” when really it’s just another installment in that stale genre. Like most papers in that genre, the IV is usually not fully justified; we just have to take on faith that it is really independent. Often, genetic confounding is plausible, but this is never discussed or considered by SSSM economists who don’t really know what heritability is.

What is wrong with Isungset paper exactly? Two possibilities. One, a rare variant theory of mutational load is plausible. Deleterious variance can be extremely rare and unique in the genome, maybe not occurring in common SNPs picked up by standard GWASs. Under this model, the Isungset method cannot rule out mutational load differences between siblings as the cause of lower younger sibling educational performance. We know these differences can explain the performance gap. Isungset admit this:

For that matter, mutations also rise with parental age, in particular with paternal age at conception (26). There is evidence that advanced paternal age increases the probability of offspring intelligence disorder, schizophrenia, and autism (35–37), as well as the rate of several other health-related traits (38).

And about rare variants, they say:

Our study has some limitations. First, PGSs are based on common alleles, and we are not able to tell if there are differences in rarer variants. That said, If rarer variants in the form of de novo mutations were importantly associated with birth order, the most obvious explanation would have involved parental age, and this is contradicted by our findings regarding maternal age

What is this about maternal age and mutation they find? Strange, mutational load is mainly transmitted by the father and not the mother, so they are controlling for the wrong parental age. Let’s see if their reasoning is valid here.

They reason that Figure 1 results are not consistent with mutational load, but are consistent with the SSSM.

There is a flaw here. Do you see it? The results are also consistent with older first time mothers being smarter/more educated. They do not control for mother PGS/EA/IQ. Ouch. In fact, we know more educated women have kids at a later age. This has confounded research into the mutational effect regarding IQ; only one study to my knowledge has controlled for this properly, and it found a much higher effect than you find from not controlling for it. [EDIT: see the bottom of the article, very last paragraph, I believe this reasoning is mistaken as I did not see that they employed family fixed effects. Interestingly, if mutational load is positively correlated with EA due to leftism predicting EA, and its negative effect on IQ being smaller than its positive effects on personality traits positively correlated with EA, then this paper still fails to provide evidence for any environmental effects.]

Power failure. When they control for everything but paternal age, they get null results. The p values are shit; womp womp. Not “compelling evidence.”

With this kind of power, even without a rare alleles model, they actually fail to find a birth order effect that is independent from parental PGS.

They also lack the power to test mutational load theory even without a rare variants model. See panel B above, some promising results, but the p values are bad and there’s no attempt to control for parental PGS in the paper.

Overall, I would say this paper does not seriously engage with mutational load theory and its conclusions are not supported by the data in the paper, a usual occurrence in SSSM research (see chapter 4 here for a case study of brain development research from 2000 to 2020 where this problem is widespread and all-encompassing).

Bird’s other citations just show that there is a birth order effect, so not seriously engaging with mutational load theory. I conclude that Bird’s claims about birth order effects being shared-environmental in nature are far from conclusive and are based on insufficient evidence that is improperly trumped up as much better than it really is in Bird’s post.

That said, I believe Bird makes a correct, though well-known point about social outcome traits; that genetics is predominate but shared environment can have a small, but measurable effect on these.

Edit: Am I wrong because of fixed effects?

Emil Kirkegaard in the comments below says “It cannot be a between family confounding factor, as you are suggesting” because of family fixed effects.

From Mostly Harmless Econometrics, it would seem this means that the model is like this:

(Ignoring sex as it should be irrelevant to the following analysis, assuming maternal age and birth order do not affect sex). The fixed effects are the family vector; the length of the vector is the number of families. It’s all 0s except for the family each person belongs to.

Angrist and Pischke point out this model estimates the same betas as the following:

Where bar denotes the family average for person i. This is because the family average of the fixed effect is just the fixed effect itself, as it has no variance within a family.

I’ll denote this model like this:

Now we can analyse what happens to B_o in a family fixed effects model when you add in M hat, using the OVB formula.

Specifically, we want to know the sign of what we’re adding onto “long.” It should be positive merely given the fact that older first time mothers are smarter.

Is this positive?

Because the data is given with sibship always controlled for, we can say that average sibling order does not vary. Sibling order will also not correlated with average maternal age; later siblings have the same average mother age as earlier siblings. This leave the first term.

This is positive, since people with later birth order tend to have older mothers.

Now, is the other term positive? It can be broken down likewise:

Hmmm, this calls for wisdom. My contention is that when maternal age correlates with educational attainment (we know it does empirically), that this term will be positive, thus rendering the analysis confounded even with family fixed effects.

According to GPT simulation, this term is always positive when the correlation I mentioned is positive.

Unless this method is not at all what they mean by family fixed effects, or there is a logical flaw here, I conclude that family fixed effects does not replace observing mother genetics. They showed that maternal age should correlate positively with educational attainment. This does not contradiction mutational load theory, because family fixed effects does not specifically “control for genetics”. Any positive correlation between maternal age and EA for any reason, including older first-time mothers being smarter genetically before reproducing, should produce this result, even under “family fixed effects”. The result observed in the paper is still consistent with mutational load theory, as the negative effect of birth order can still be because of mutational load, as long as first-time mothers become smarter as their birth age goes up faster than their mutation effect goes up with age (this is the case for couple age and IQ).

In contrast, if we had the short and the long models:

I would say the effect of omitted in long would be slightly negative due to mutational load, as mother’s gene score is present in the model, so the independent effect of mother age in long will no longer be positive. The regression of omitted on included should be positive, so here short < long. If the effect of birth order in short is negative, then the effect of birth order with mother added in should be less negative, greater than short, which is consistent with ML theory. Their fixed effects model is not this model.

Further edit: I don’t understand yet why we couldn’t do the same averaging trick with the gene score model, if the mother gene scores are always the same for each kid. However, on GPT simulation, my logic is reproduced. Adding M to the fixed effects model with no gene scores gives a positive M effect under ML theory assumptions about the variable relationships, and a more negative O effect, while adding M into the mother gene score model gives a negative M effect and a more positive O effect. Intuitively, I think this is because mother gene scores reveal similarities between families, while fixed effects do not detect if two families are similar or not. Two families can have the same mother gene scores, but they will not have the same fixed effects.

Edit again:

The above GPT simulations were flawed, don’t trust GPT with simulations. Disregard pretty much the whole argument above. I’ll keep it up for transparency but my hand-crafted code and the contradiction with the gene scoring model I being the same as fixed effects using the mean differencing trick has made me change my view here. My hand-crafted simulations show dummy fixed effects is the same as mean-differencing and this should, as my intuition says, give the same results as controlling for mother’s gene score. Under simple mutational load + no environmental influence theory, a mother waiting longer to give birth to you (i.e. the effect of her age independent of birth order) should have a negative effect on your relation to the family mean of education, yet it has a positive effect in the study. This does not falsify mutational load theory. Either mutational load positively correlates with educational attainment, despite correlating negative with IQ, or it correlates negatively with EA, but some environmental effect of older mothers is stronger.

wanna hear a joke? how do U redpill people?

U cant because of thier mutationbal load hahahahahHAhaha

Needlessly hostile article. Confusing to call him Bird when there's already a communist Kevin Bird in this area. IB would be better, which also happens to be a Danish male first name. :)

https://academic.oup.com/pnasnexus/article/1/2/pgac051/6604844?login=false#381345265

"We use family-level fixed effects when estimating the bivariate association between birth order and these outcomes, meaning we are comparing siblings within the same family."

It cannot be a between family confounding factor, as you are suggesting.

Shared environment cannot differ between siblings. By definition, shared environment is whatever causal forces that make family members more similar that aren't genetic.