On the Origins of Civil Rights Law

Applying exousiology to historical analysis

A major fruit of exousiology should be scientific history, or, in other words, a scientifically supported historical method. Such a method should be based on knowledge of who had what power at any given time and which factors explained variance in agent motivation (genes, environment, information, etc). This knowledge, to whatever extent it is held with certainty, provides enough information for a historian to state who was responsible for what changes in the social state (who had the power to do it) and why (how did motivational factors change through time such that this agent or set of agents were produced?). Exousiology has now developed to the point where we can begin our first attempt at a scientific account of history: through credit theory, political agency theory, and our emerging knowledge of alpha, we can begin to shed light on the who question, and through our variance component model and our emerging knowledge of memetics, we can begin to articulate why.

Like the manuscript, this should be considered a “beta” article. In fact, it will probably be appended to the beta 1.2 edition of the manuscript, where it will be updated in subsequent editions. The purpose of writing this article now is twofold: first, exousiology is already advanced enough to shed some much needed light on recent history. Second, despite whatever shortcomings it may have, this exercise will help theoretical exousiology develop in useful directions, as it will help identify gaps in knowledge and modeling that are relevant to applying exousiology to historical methodology.

The first event to analyze, the 1954 Brown vs. Board, has been chosen for its discreteness, its relevance to the present day, and its huge importance at the time. These factors lend themselves to easy analysis, because it means that there is no lack of sources from the time in question through to the present day discussing and analyzing the causes and consequences of this event.

In this article, we will sketch out a chain of events leading up to the passage of the Act, while providing novel insight from exousiology where applicable. We will [probably] be left with many questions, and these will drive future articles on the topic, updates to this article in subsequent editions of the manuscript, and future research in exousiology.

What happened?

Wikipedia gives a good summary of what happened:

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954),[1] was a landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segregated schools are otherwise equal in quality. The decision partially overruled the Court's 1896 decision Plessy v. Ferguson, which had held that racial segregation laws did not violate the U.S. Constitution as long as the facilities for each race were equal in quality, a doctrine that had come to be known as "separate but equal".[note 1] The Court's decision in Brown paved the way for integration and was a major victory of the civil rights movement,[3] and a model for many future impact litigation cases.[4]

The underlying case began in 1951 when the public school system in Topeka, Kansas, refused to enroll local black resident Oliver Brown's daughter at the elementary school closest to their home, instead requiring her to ride a bus to a segregated black school farther away. The Browns and twelve other local black families in similar situations filed a class-action lawsuit in U.S. federal court against the Topeka Board of Education, alleging that its segregation policy was unconstitutional. A special three-judge court of the U.S. District Court for the District of Kansas rendered a verdict against the Browns, relying on the precedent of Plessy v. Ferguson and its "separate but equal" doctrine. The Browns, represented by NAACP chief counsel Thurgood Marshall, then appealed the ruling directly to the Supreme Court.

In May 1954, the Supreme Court issued a unanimous 9–0 decision in favor of the Browns. The Court ruled that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal", and therefore laws that impose them violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. However, the decision's 14 pages did not spell out any sort of method for ending racial segregation in schools, and the Court's second decision in Brown II (349 U.S. 294 (1955)) only ordered states to desegregate "with all deliberate speed".

In the Southern United States, especially the "Deep South", where racial segregation was deeply entrenched, the reaction to Brown among most white people was "noisy and stubborn".[5] Many Southern governmental and political leaders embraced a plan known as "Massive Resistance", created by Virginia Senator Harry F. Byrd, in order to frustrate attempts to force them to de-segregate their school systems. Four years later, in the case of Cooper v. Aaron, the Court reaffirmed its ruling in Brown, and explicitly stated that state officials and legislators had no power to nullify its ruling.

This event neatly encapsulates principles of exousiology including the process of political agency, the Patriciate, basis of power, and variance components of behavior. For example, the case began with organized political agency. This is somewhat obscured in the above summary and in elementary school tellings. The case was in fact planned out and implemented by NGO elites; it costed money and required recognition, advocation, and implementation. Reviewing the explicit motivations of these agentic elites should give interesting insight into why this event occurred.

The Supreme Court can be modeled as a Patriciate. While the Supreme Court is not identical to the true ruling class of society, it can be considered a representative fractal instance of it, as it has a basis of power (an uptake mechanism that selects for certain traits that might change), it is coordinated and centralized, its members change over time, and the variance of its political behavior at a time and through time can in theory be broken down into genetics, information, and other environmental factors. Finally, they are also relatively sovereign, that is, unbothered by marginal influence. This is explicitly by design; justices generally do not need to worry about money, elections, or retribution. While a constitutional amendment can overturn a Supreme Court verdict, justices are not supposed to have to worry about their pay, opportunity costs, or losing their position.

We therefore have two groups to analyze: those who created the case, and those who ruled in its favor.

Applied Exousiology

In general, because of the way political agency works, no change is really democratic. In other words, what does not happen is this: the People meet in salons frequently where they passionately and intelligently discuss the politics of the day. Through discussion, a reasonable, agreed upon update to policy that the People project will improve society for the majority emerges. This policy preference is then transmitted to the representatives of the People who then pass it into law. This is what we call the idea of the high political agency democracy.

Instead, we live in a low political agency oligarchy. This means that most people, more than 95%, are too unintelligent and docile to engage in original political behavior. The reality is that a small caste of intellectual elites generates the new ideas, does the work of spreading them, and implements them. Part of the competition between these elites is managing the non-elites, most of whom are too dumb to understand the new ideas in themselves.

Elites must generally use power to stabilize changes that are negative for the masses. Otherwise, counter-elites could outcompete the existing elites by gaining the allegiance of the injured masses. We currently model this as credit expenditure. The specific dynamics of negative changes are not fully mapped out, but will be in the future.

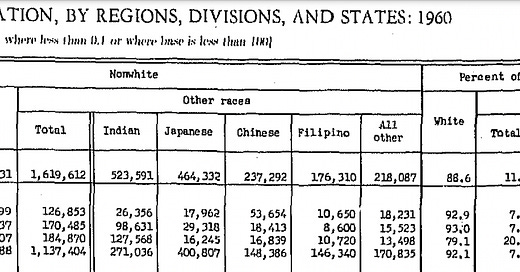

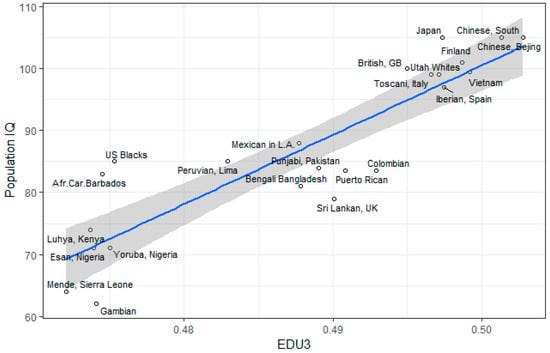

In the case of civil rights, the North had very small Black populations and consequently little history of segregation, and so were more or less isolated from any feedback regarding civil rights policies.

In 1964, after decades of elite campaigning, just 61% of Northern voters “approved” of the civil rights bill. It is unclear what percent would have shown up to a referendum and voted “yes.” That number is almost certainly bounded by the 61% figure, since “approved” can mean either that or “I will take no action against the new law at the polls,” which is not the same as taking action for the law at the polls.

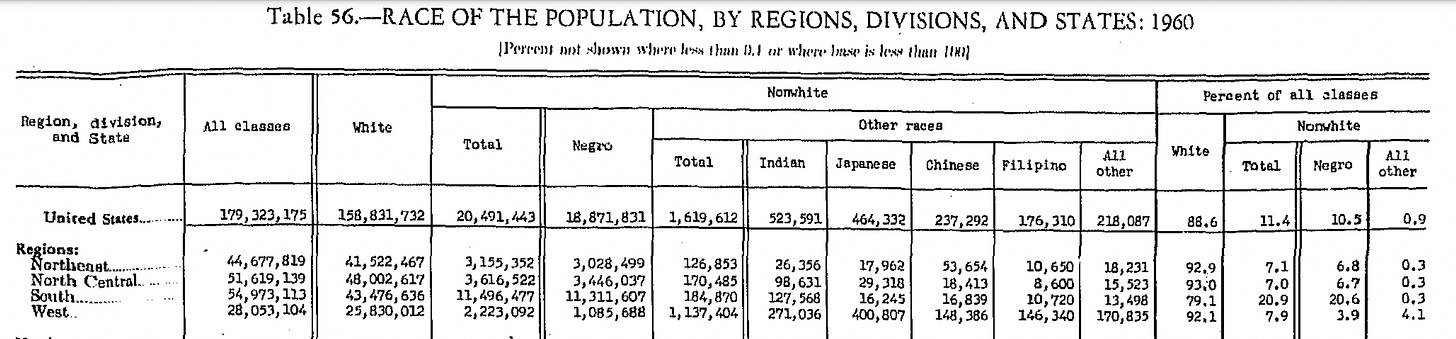

Meanwhile, elite opinion management was nowhere near as effective on Southern Whites, who actually lived around Blacks. A super-majority were against the 1964 law when it passed. Like with the 1954 decision, there were many mobs and riots that had to be forcefully suppressed by mercenaries.

This is, of course, because desegregation is just a tax on white people. White people, even those that think they are pro-Black, don’t actually want to live around Blacks. We know this because of White flight. Segregation is when these White people tell Blacks that they will not live around them, and if Blacks try to move in, they will remove the Blacks with legitimate, democratic force. Integration is when the federal government will murder you over this, so you have to pay to leave when Blacks move in and you can’t remove them.

The tax was most severe on Southern populations, and they opposed it proportionately. The tax was a subsidy for Black people, and likewise they nearly universally supported it.

Note that a decent model for this is White Approval = -1.5(Percent Black) + 70. If White Approval is a phenotype, and P = G + E + M, and the relevant genetics are the same between Northerners and Southerners, then P = E + M. If there is no variance of propaganda (M), and the relevant environmental factor is percent black, then the 70 term from the line is the power of power, given that the natural intercept is 0, since civil rights does not benefit Whites who are not around Blacks.

Per credit theory and the fungibility assumption, work equivalent to just pumping money into the population such that 61% of the damages are covered in 6% Black places and 24% of the damages are covered in 30% Black places is occurring.

The median home price in 1960 was $12,000, or about $120,000 in today’s money. A 2004 paper found that for every 3 percent increase in Blacks in a neighborhood, home values lose about a percent of their value. Therefore, Southerners were to lose about 10% on average, and Northerners about 2%, which amounts to $1200 each for Southerners and $240 each for Northerners. This amounts to over $50 billion total in 1960 dollars — a lot of money, more than $2.5 billion per year if it was spent from 1944 to 1964.

That’s a lot of credit. It goes to show how truly massive the push for Black gibs was. And the figure makes sense — consider the current yearly budget of the NAACP alone is $25 million. If we interpret Franz Boas and his ilk as essentially working full-time just to get Black people gibs, there comes millions, if not billions (accounting for opportunity cost), of dollars.

Then there’s Hollywood, the media, and others. Who was combatting this? The Pioneer fund? The KKK? These figures suggest that, among elites, there was truly broad support for Black gibs. It is therefore misleading to blame just the Supreme Court, or just the NAACP — the true answer must be found in broad factors relating to elite recirculation and general phenotype change over time. Nevertheless, perhaps tracing the key event can shine light on these factors.

The event

The case was created by the NAACP.

Thurgood Marshall and NAACP officials met with Black residents of Clarendon County, SC. They decided that the NAACP would launch a test case against segregation in public schools if at least 20 plaintiffs could be found. By November, Harry Briggs and 19 other plaintiffs were assembled, and the NAACP filed a class action lawsuit against the Clarendon County School Board: Briggs et al. v. Elliott et al. Briggs v. Elliott became one of the cases consolidated by the Supreme Court into Brown v. Board of Education.

They had decided to go around and create lawsuits after the Supreme Court in 1948 had ruled in Sipuel v. Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma that because there was no other state law school, Blacks had to be admitted to the White law school in order that they may have equal facilities provided by the state.

By 1954, the Supreme Court had 5 FDR appointees, 3 Truman appointees, and 1 Eisenhower appointee. The opinion is a good primary source explaining the Court’s motives. Its logic is truly astounding — it is fundamentally a radical departure from old “separate but equal” doctrine, based on no update to the Constitution:

Segregation of white and Negro children in the public schools of a State solely on the basis of race, pursuant to state laws permitting or requiring such segregation, denies to Negro children the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment-, even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors of white and Negro schools may be equal.

This seemingly contradictory statement, that even though everything is measurably equal, school segregation denies Blacks equal protection of the law, in contradiction to 80 years of precedent, is based not on an amendment to the Constitution — no, the relevant law was the same as 80 years prior — but rather it is based on new pseudoscience and the popular arguments of the times.

In particular, the Court discovers the never-before known right to not feel inferior, as well as the right to education, and then cites studies showing that segregated education makes Negroes feel inferior, and this interferes with their education, like stereotype threat.

Today, education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments. Compulsory school attendance laws and the great expenditures for education both demonstrate our recognition of the importance of education to our democratic society [source: dinner parties with the NAACP]. It is required in the performance of our most basic public responsibilities, even service in the armed forces. It is the very foundation of good citizenship. Today it is a principal instrument in awakening the child to cultural values, in preparing him for later professional training, and in helping him to adjust normally to his environment. In these days, it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education. Such an opportunity, where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a right [source: definitely not the Constitution] which must be made available to all on equal terms.

To separate them from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their -hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone. The effect of this separation on their educational opportunities was well stated by a finding in the Kansas case by a court- which nevertheless felt compelled to rule against the Negro plaintiffs:

"Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law; for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the negro group. A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to learn. Segregation with the sanction of law, therefore, has a tendency to [retard] the educational and mental development of negro children and to deprive them of some of the benefits they would receive in a racial [ly] integrated school system."

Whatever may have been the extent of psychological knowledge at the time of Plessy v. Ferguson, this finding is amply supported by modern authority.

[Cites: K. B. Clark, Effect of Prejudice and Discrimination on Personality Development (Midcentury White House Conference on Children and Youth, 1950); Witmer and Kotinsky, Personality in the Making (1952), c. VI; Deutscher and Chein, The Psychological Effects of Enforced Segregation: A Survey of Social Science Opinion, 26 J. Psychol. 259. (1948); Chein, What are the Psychological Effects of Segregation Under Conditions of Equal Facilities?, 3 Int. J. Opinion and Attitude Res. 229 (1949); Brameld, Educational Costs, in Discrimination and National Welfare (MacIver, ed., 1949), 44-48; Frazier, The Negro in the United States (1949), 674-681. And see generally Myrdal, An American Dilemma (1944).]

Strangely it seems that the Court was either not honest or intelligent enough to realize the fundamental contradictions inherent in what they are saying. For one, they somehow believe that separating the races generates inferiority in Blacks, but not Whites:

We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

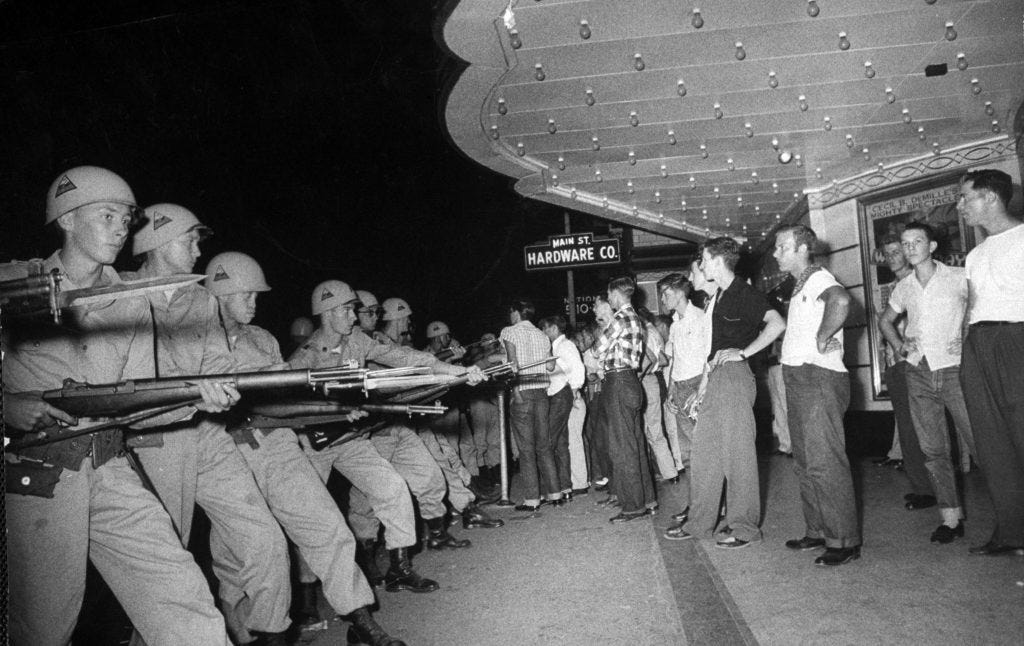

But if the difference between two identically funded and staffed educational facilities is the race of the students, and the Black school is inherently inferior, and the White school is not, what does that make Black students? Inherently inferior students. Which, not to be a wignat, but this is genetically the case on average:

Second, does not school itself generate a sense of inferiority in all students? It necessarily does, because school renders students virtually inferior to teachers, who are themselves quite naturally low. But if school instills feelings of inferiority, and feelings of inferiority are contrary to education, is not school contrary to education? Is not the right to school a violation of the right to education and the right to not feel inferior? It necessarily is.

It seems that the Court’s incoherent opinion can be traced back to the deception-power of the education system, in particular to the idea that school is good for society and a body of pro-Negro work which can be summed up as race-denialist and blank slatist.

Is this a win for info-determinism and Cathedral theory? Not so fast. Perhaps the success of Black gibs was heavily mediated by memetics and academic output. The historical evidence appears to show this. Both sides claim this. For instance, from Race and Reason, an anti-integration text:

The author, Carleton Putnam, wrote a letter against the 1954 decision, and in response received thousands of letters. These letters convinced him that the core reason why the Northern public supported the decision was that they believed that Blacks were as genetically intelligent as Whites, an idea which is blatantly false. He blames this on academic work like that cited by the Court.

It would appear that the costly work being done to shift the public’s opinion from not approving of Black gibs to what we see in Figure 1 is mostly in the form of propaganda. Propaganda requires labor to create and spread. The Supreme Court can perhaps best be modeled as being under the power of this propaganda.

The question now becomes, from whose alpha and agency did the propaganda campaign emerge? What motivated them?

That will have to be addressed in the next part, due to the length of this post. If you would like to find out, make sure you subscribe:

There was this guy who did an analysis of 70 metropolitan areas, finding that for every black family that moved into a central city between 1940 and 1970, two white families moved out:

https://archive.is/ajt1Z

https://not-equal.org/content/pdf/misc/10.1515_9781400882977.pdf