Political science is not a fully scientific field. This is trivial to demonstrate. In general, the textbooks for the field are sparse, opinionated, and lack certainty. Nothing much is known for sure in the field. “Perspective” in emphasized over real findings. This is a sign that a field is not a developed science. Developed sciences have canonical findings; pre-sciences do not. One of the best textbooks I have found is a “handbook”, meaning it contains a lot of diverse perspective instead of a unified consensus, as there is no unified consensus in the field, because it is not fully scientific.

Another sign of an immature field is its level of mathematical rigor. In the handbook we find the first two parts after the introduction concern “political theory” and “institutions.” We are told, essentially, the political theory is fake activism.

Political theory is an interdisciplinary endeavor whose center of gravity lies at the humanities end of the happily still undisciplined discipline of political science. Its traditions, approaches, and styles vary, but the field is united by a commitment to theorize, critique, and diagnose the norms, practices, and organization of political action in the past and present, in our own places and elsewhere. Across what sometimes seem chasms of difference, political theorists share a concern with the demands of justice and how to fulfill them, the presuppositions and promise of democracy, the divide between secular and religious ways of life, and the nature and identity of public goods, among many other topics.

Having a “humanities end” of your discipline is an admission that the subject is not a full science. Physics has no such end.

Now for institutions. For years I have criticized political scientists for taking institutions and their rules for granted. In analyses I saw, there was never any attempt to explain why institutions exist. When pressed on this, “institutionalists” would appeal to a kind of Rawlsian rational founding myth, or a social contract myth, where the rules are laid out in some kind of other-worldly Agarthic constitutional convention; these rules are completely binding and everything to do with the state consequently is explained by its official rules. I have said, the rules are not real, they are always changing, institutions are “not real”, they are just individuals behaving; we must explain why they behave in this patterned way we call a “state” or a “company.” There is no such explanation found in institutionalism, even though one would think this is the primary job of political science.

Sometimes I was told I was strawmanning or being unfair. I have thought, maybe I am strawmanning, because I am not very well read in traditional political science. Nevertheless this is what I have absorbed from interacting with them.

But now I read this:

The study of political institutions is central to the identity of the discipline of political science. Eckstein (1963, 10–11) points out, “If there is any subject matter at all which political scientists can claim exclusively for their own, a subject matter that does not require acquisition of the analytical tools of sister-fields and that sustains their claim to autonomous existence, it is, of course, formal-legal political structure.” Similarly, Greenleaf (1983, 7–9) argues that constitutional law, constitutional history, and the study of institutions form the “traditional” approach to political science, and he is commenting, not criticizing. Eckstein (1979, 2) succinctly defines this approach as “the study of public laws that concern formal governmental organizations.”

The formal-legal approach treats rules in two ways. First, legal rules and procedures are the basic independent variable and the functioning and fate of democracies the dependent variable. For example, Duverger (1959) criticizes electoral laws on proportional representation because they fragment party systems and undermine representative democracy. Moreover, the term “constitution” can be narrowly confined to the constitutional documentation and attendant legal judgments. This use is too narrow. Finer (1932, 181), one of the doyens of the institutional approach, defines a constitution as “the system of fundamental political institutions.” In other words, the formal-legal approach covers not only the study of written constitutional documents but also extends to the associated beliefs and practices or “customs” (Lowell 1908, 1–15). The distinction between constitution and custom recurs in many ways; for example, in the distinctions between formal and informal organization. Second, rules are prescriptions; that is, behavior occurs because of a particular rule. For example, local authorities limit local spending and taxes because they know the central government (or the prefect, or a state in a federation) can impose a legal ceiling or even directly run the local authority.

Eckstein (1979, 2) is a critic of formal-legal study, objecting that its practitioners were “almost entirely silent about all of their suppositions.” Nonetheless, he recognizes its importance, preferring to call it a “science of the state”—staatswissenschaft—which should “not to be confused with ‘political science’” (Eckstein 1979, 1). And here lies a crucial contrast with my argument. Staatswissenschaft is not distinct from political science; it is at its heart.

This is an acknowledgement of what I noticed, and also of the fact that these people tend to gaslight about it when pressed, like Standard Social Science Model people in general.

This is likely because the SSSM is partly dishonest, partly irrational. When made logical and clear, the irrationality and dishonesty are exposed, and this is embarrassing, so practitioners deny that they believe for example that “biology is unimportant to understanding behavior.” Then they go back to ignoring biology is all of their studies, showing their effective view is indeed that biology is unimportant to understanding behavior.

Invading political science

Since this is the norm in political science, perhaps the field is ripe for a shakeup, a paradigm shift, or even a scientific revolution. If we view the field as a marketplace of ideas about states, power, and politics, maybe we can apply startup-logic to such an invasion. Peter Thiel talks about how radical shakeups are fueled by secrets that current providers don’t know or can’t accept. I think I know a few “secrets” that the vast majority of political scientists don’t know:

Biology is the prime determinant of human behavior

After that, probably economic pressures

Wealth is power

A science is its verified mathematical models

Use probability and statistics to measure uncertainty and model error. Avoid deterministic calculus models.

I think if most current political scientists believed these and could execute on them, the field would already look like how I imagine it can.

A theory of democracy

Let’s apply these secrets to democracy. Just what is democracy? How can we predict where it will be and when it will fall? Applying the secrets, we want to break democracy down into a mathematical model based on human biology, wealth, and economics. This model should be estimatable, meaning its parameters can be measured, unlike traditional neoclassic economics “models.”

Applying secret 1, we can predict that some populations lack the biology for democracy. In other words, some races can’t be democratic without biological evolution. The biggest trait involved is probably IQ, and after that social conservatism or some sort of conformity factor. If this is true, we could predict, unlike political scientists, that Iraq and Afghanistan would never be democracies. If gene flow of less democratic races enters a more democratic race, democraticness will fall.

Applying secret 2, let’s hold race constant and just look at white people. What predicts more or less democracy within whites? I hypothesize it’s the distribution of resources; democracy is about formally acknowledging a spread out distribution of power. If power is just wealth (secret 3), then democracy just recognizes a relative egalitarian wealth distribution.

This should mainly predict deviances of democraticness within self-claimed white democracies. Some democracies are more democratic than others. This within-democracy deviance, within a race, should vary mainly with wealth concentration,1 if this theory is correct. If this is true, then we can devolve down to economics, which can be flattened to biology with theories like Smart Fraction Theory.

Applying secrets 4 and 5, we want to translate these into math, ideally probability. This is pretty simple, a basic regression can verify these ideas.

Where D is democraticness, R is race, W is wealth concentration. In theory the betas are positive and the variance explained is quite high. If it is too low, we need to look for other factors.

Is there anything to this theory?

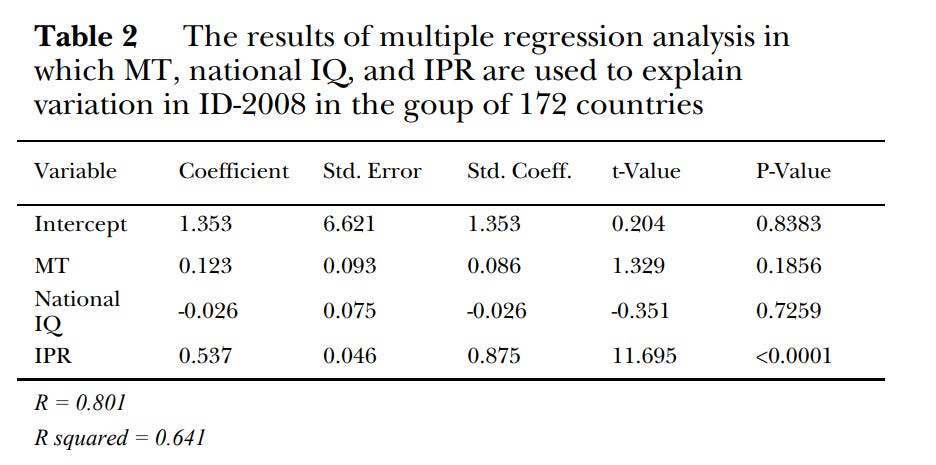

Yes. The only analysis I can find is from 14 years ago in Mankind Quarterly.2 It looks promising, explaining 64% of the variance with MT (a race proxy, Median Temperature), national IQ, and IPR (resource concentration). This should have been followed up on with a better measure of race, and then race should be broken down into the specific racial characteristics thought to cause the association.

Political scientists, of course, never did this, because on average they’re allergic to race. That leaves this an open area of research. Maybe someone will pursue it.

Vanhanen in Democratization: A Comparative Analysis of 170 Countries reports that there is a well-known association between democraticness and economic development (pg. 8). However, this is corrupted by SSSM heuristics. “the usual explanation [is] economic development produces the middle class, which is the primary promoter of democracy, whereas the upper class, and especially the lower class, are seen as the enemies of democracy.” (pg.9). The idea that “democracy concerns power, and democratization represents an increase in political equality. Therefore, power relations determine whether democracy can emerge, stabilize, and then maintain itself. Capitalist development tends to change the balance of power among different classes and class coalitions. Industrialization empowers subordinate classes and makes it politically difficult to exclude them” (pg. 9) is a dissent position. And of course, but a handful dare to add in anything about race.

The author was Tatu Vanhanen. He apparently knew Richard Lynn and was a political scientist in Finland. It would seem we independently came to the same ideas; I found his article after forming these hypotheses. The race part is pretty easy to come to, of course. The resources part is less intuitive and my path to it is more interesting. First, I read a lot of elite theory, but this was mostly a waste of time. Still, it taught me there wasn’t much out there to compete with in this field. Then I did a lot a thinking and basically reasoned that the most logically coherent, Occam’s razor following model of power is one that just reduces it to resources, which is known as wealth in humans. This is contrarian as it is more popular today to believe in a Pantheon of different “types” of power. I later found out this mirrors the concept of resource holding potential, which is good because I wasn’t thinking as biologically as I should have been but the product turned out similar nonetheless. Next, I reasoned that whether a country is democratic or not reflects its “real” power distribution, which is to say it reflects the wealth distribution, which is of course thought to mostly be a function of biology (smart fraction and so on) and perhaps some exogenous economic factors. This is determined prior to institutions, and institutional rules, like voting laws, come to reflect this “real”, and not “symbolic” or “constructed”, distribution of resources. In theory, nominal democracies will also vary from true democraticness precisely to the extent that wealth is concentrated; the richer the “rich” is, the more they can mess with elections and influence politicians directly. At complete wealth equality, there is no way to mess with elections. In the middle, elections take place but strong top down incentives constrain politician action. At the extreme, the wealthy rule directly and we call it an autocracy, no point in bothering with elections because the masses are so powerless. It’s nice to see someone else came up with a similar view independently, it gives more weight to the ideas. It’s a shame political scientists have neglected his work just as SSSM people neglect hereditarian work generally.

Finally old Bronski is back.

Among the factors that predict more or less democraticness among whites I believe is clannishness.