The possible origins of the Modern Western European Marriage Pattern

Was everyone before 1600 AD a pedophile?

Alert: I have a new X account. Refollow me on X here.

We finished off last time with a time traveling Roman man, who arrives in the 21st century and is curious about why everyone is unhappy and nobody is getting married in their teens, even while billionaires fret about the “fertility crisis.” Our Roman comes from a world of universal early marriage. It wasn’t just Rome — it was all ancient societies we have data for.1

It’s not hard to see why early marriage would be universal. In a competitive ecosystem, people who marry earlier will reproductively outcompete those who marry later. While small differences in the age of marriage won’t lead to huge differences in fertility, large age differences will. The contemporary marriage pattern is a huge difference from the ancient marriage pattern. It sacrifices about 75% of the female fertility window, with women marrying very late, at an average age of 30, compared to an ancient 15-17.

The more interesting question is: “how could late marriage emerge and persist at all?” Before we generate some hypotheses, let’s map out the timeline of the emergence of late marriage.

Hajnal and the Modern Western European Marriage Pattern

In his classic 1965 paper, John Hajnal defined the “European Marriage Pattern”. This name is a misnomer. It’s not the European marriage pattern. It’s a Western European marriage pattern. Specifically, it’s the modern Western European marriage pattern. Some writers call it the WEMP, the W standing for Western, but we will call it the MWEMP to be even more precise.

Hajnal writes:

The uniqueness of the European pattern

The marriage pattern of most of Europe as it existed for at least two centuries up to 1940 was, so far as we can tell, unique or almost unique in the world. There is no known example of a population of non-European civilization which has had a similar pattern.

The distinctive marks of the 'European pattern' are (1) a high age at marriage and (2) a high proportion of people who never marry at all.2 The 'European' pattern pervaded the whole of Europe except for the eastern and south-eastern portion.

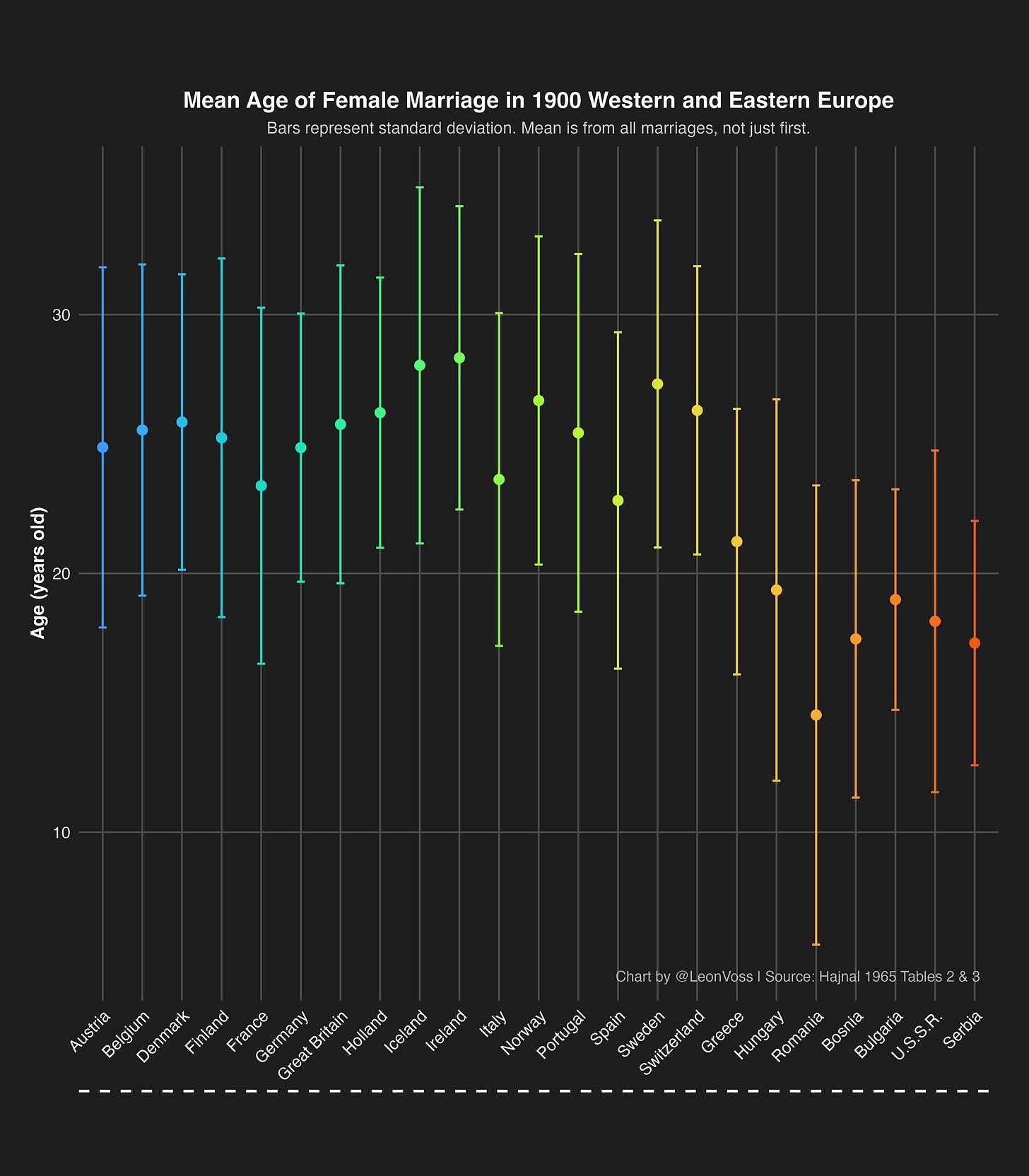

Let us consider data for 1900. The European pattern extended over all of Europe to the west of a line running roughly from Leningrad (as it is now called) to Trieste. The European pattern may be seen in Table 2 below. On the other hand, the countries east of our imaginary line are shown in Table 3.

This last paragraph defines the classic “Hajnal line”, pictured below.

Here is a chart depicting Hajnal’s tables:

The means and standard deviations are constructed using the table percentiles, assuming marriage age is normally distributed. One can imagine two lines, one at the age of 16 or 17 and one at the age of 25. MWEMP countries tended to marry women above the age of 25, while Eastern countries did not, and Eastern countries tended to marry women under the age of 17, while MWEMP countries did not.

It’s also easy to see that, except for Greece, all of Hajnal’s Eastern examples have marriage means in the teens, while all of the Western means are in the mid twenties.

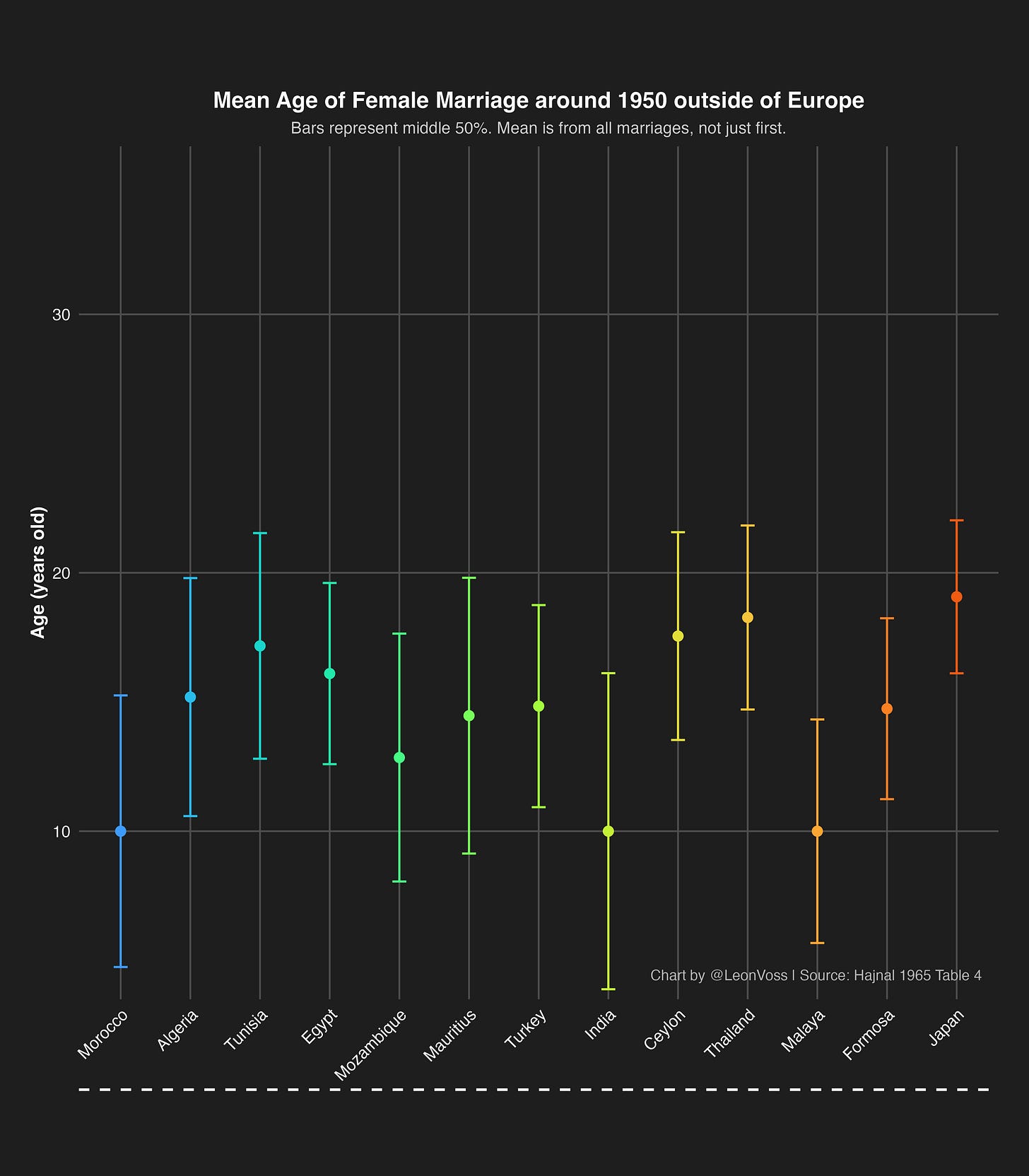

Hajnal goes on to examine the rest of the world around the time he was writing.

All other countries had means in the teens. Some practiced child betrothal. The MWEMP was, in fact, unique in the world. While in the 21st century, many non-Western countries have marital means above the teens, and many Western countries have marriage means in the thirties, historical deviation from teenaged marriage started with the MWEMP. The simplest hypothesis is that whatever caused the MWEMP also causes contemporary marriage postponement. Our Roman time traveller would therefore be wise to begin his study of late marriage with investigating the causes of the MWEMP.

The Origins of the MWEMP

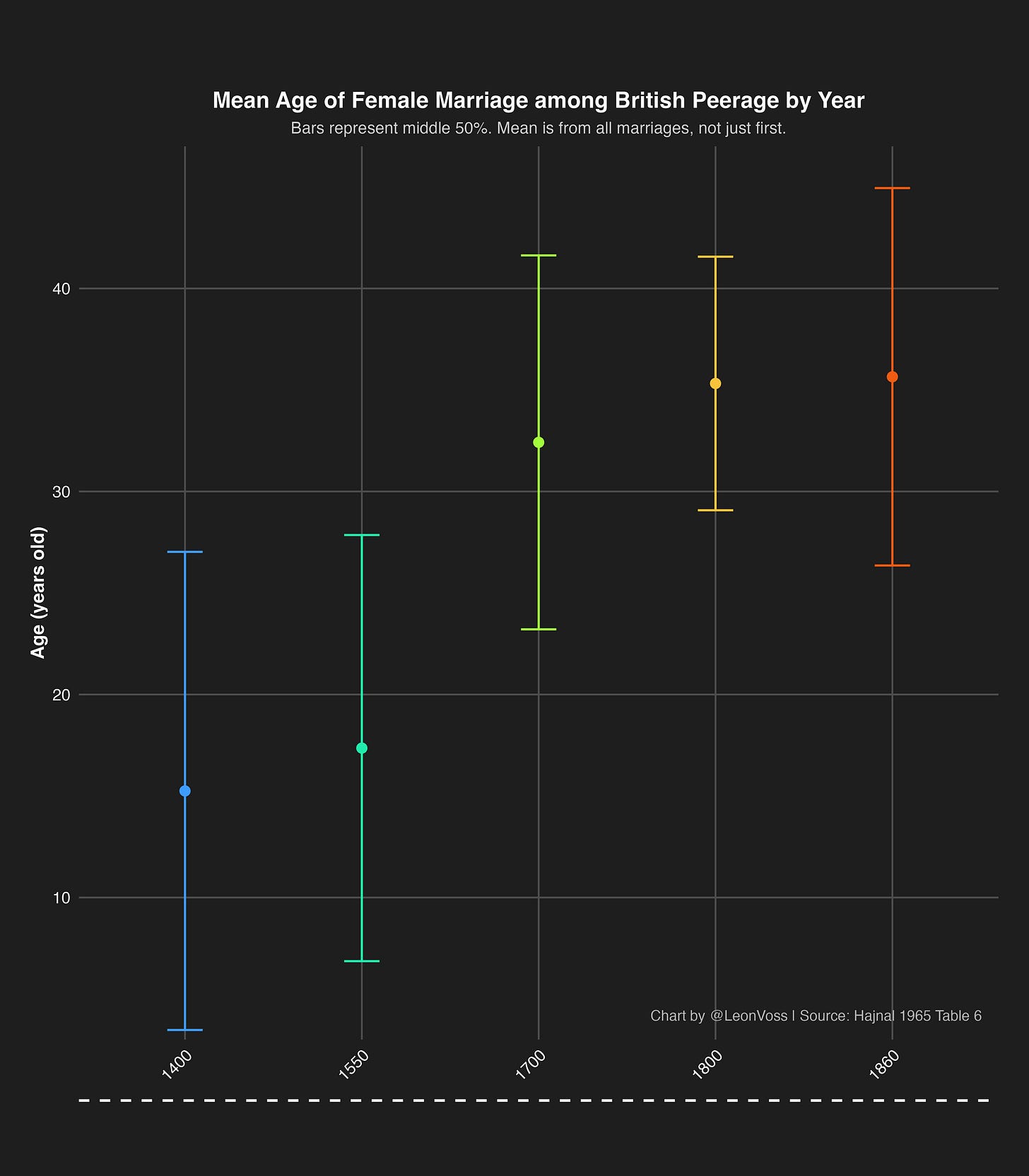

Hajnal demonstrates in the latter part of his paper that the MWEMP emeged during early modernity.

Until about 1700, for example, the British peerage practiced what we can at this point name the Historical Marriage Pattern (HMP), which is charactized by teen marriage being average, child marriage being tolerated, and marriage beyond the early twenties being uncommon or very rare.

Thereafter, they switched to an extreme version of the MWEMP, which seems to more closely resemble the timeline of the PMP, or Postmodern Marriage Pattern, which is characterized by frequent geriatric marriage with a mean near or over 30. In contrast, the MWEMP was an intermediate pattern, wherein marriage would most commonly occur between 20 and 29, with a mean near 25.

Considering that it would seem the PMP is just the world catching up to the aristocratic variant of the MWEMP, it is quite likely that whatever caused this shift to first occur a few hundred years ago in Western Europe among the upper classes is the same as what is causing marriage to become delayed increasingly around the world today. Just what could that be? In his article, Hajnal has no idea. The data to figure out the cause just wasn’t available to him — it was groundbreaking enough at the time to point out that it happened.

Evolutionary priors lead us to surmise that perhaps delayed marriage was adaptive. Today people prattle ever on about how much a teenage pregnancy will destroy your life. Some people even believe that teen pregnancy is harmful to the baby and dangerous to the mother.3 Perhaps when marriage was able to be delayed due to sufficient economic circumstances, those who delayed it into the 20s had greater long term fitness than those who married in their teens. Even though teenaged brides have a larger fertility window, maybe their fertility becomes exhausted, maybe they died more in child birth, maybe their children were more likely to breed less than children of twenty-something mothers.

Gregory Clark, one of the greatest living sociobiologists, addressed this hypothesis in a paper from last year.

He found there was a negative relationship between female age at marriage and her number of great-great-grandchildren. In other words, teenaged brides had higher fitness. There was no selection pressure in favor of the MWEMP.

What about selection pressure against? Clark estimates that the heritability of fertility was unusually low. By the breeder’s equation, the selection pressure must have been near zero, due to extremely low heritability. People with gene scores favoring teen marriage just couldn’t outdo people with inferior fertility predispositions.

We know the heritability was low because the fertility behavior of late breeder children was no different on average than the fertility behavior of early breeder children. Thus, neither genetic inheritance nor family environment could have explained much variance in fertility. This is highly unusual for a behavioral trait. At first it seems quite perplexing. But a simple model can explain this.

Think about how spouses met in early modernity. There were no communications technologies, and extremely limited travel technologies. They had to be extremely local. Imagine a bell curve of latent, genetic preferred ages of marriage. If you have a child, and they have to randomly roll their spouse from this distribution, on average your child will get a spouse that wants to marry at the average age of marriage. Your child’s couple latent genetic breeding age is almost always more average than your child’s score, if you are an outlier. In addition, breeding age is not the only determinant of fertility.

I have drafted a model where marriage pattern has a normal heritability of 0.40, mating is random, and couple marriage age explains 33% of fertility variance. These parameters can be further fine tuned, but for the sake of this blog post, it replicate’s Clark’s data enough — the average number of grandchildren per person fails to correlate with marriage age, but the total number of grand, great-grand, and great-great-grandchildren does correlate with marriage age. The consequence of this is an improvement in tendency to marry early gene scores of 0.05 SDs per generation. This is a quite normal selection pressure and it would be weird for latent heritability or selection pressure to be any lower.

That we don’t see a decrease in average age of marriage suggests there is some countervailing force. This force seems to be associated with increasing wealth. Hajnal remarked in his classic article that Europe was known to be the wealthiest place on Earth, already in 1500. Recall that the gene score for early mating should have been increasing in early modernity within the MWEMP area. This means for early mating phenotype to not improve, the environment must have gotten constantly worse, or some other force must have offset the selection pressure, causing the gene score to worsen or remain stable.

That other force could be mutational pressure, or potentially wealth (probably nutrition) driven epigentic effects. It seems more likely to be mutational pressure, given that adaptive epigenetic effects should improve population fitness, not harm it. But delayed marriage and subsequent reduced fertility harms population fitness by making the population size dwindle, making it susceptible to invasion and mass immigration.

The general theory of mutational load could be defined as the idea that the mutational pressure on behavioral traits in humans tends to be 0.05 to 0.10 SDs per generation in the de-optimized direction. That means that when selection pressures are as low as our model indicates, mutational pressure predominates. The main idea is that the connection between instinct and realized fertility became too weak, due to improvements in ease of living, allowing the instinct to decay. Because phenotypic variance is compressed by social effects — random mating in our example — the emergence and persistence of people with decayed instincts shifts the population mean rapidly.

The decrease in mortality could have allowed people with more mutations affecting mating behavior to breed more at later ages. Their children inherit their mutations, while the selection pressure on early mating instincts declines further. It falls increasingly under the mutational pressure, causing people who are less romantic and less adapted for marriage at a young age to build up in the gene pool. The average genetic preferred age of marriage goes up, and the dating market is clogged up with marriage delayers. Even fit people with low mutational load struggle to find a local mate who wants to marry young. This decreases their fertility and the selection pressure goes down even more, while wealth continues to go up and it becomes increasingly easy for higher mutational load people to breed at later ages.

It’s possible this dynamic, but intensified, is behind the contemporary demographic transition and Postmodern Marriage Pattern. The brief reprieve that was the Baby Boom could have been caused by World War II briefly increasing selection pressures and mortality. In future articles, I’ll be examining the Postmodern Marriage Pattern, demographic transition, and Baby Boom. I’ll also write up a preprint, which I’ll later blog about, on the model mentioned in this article. If you don’t want to miss out, make sure you subscribe:

Heretical Insights noted Babylonian slaves married later, near MWEMP ages. One could say a MWEMP marriage was a genuine slave-poverty marriage experience.

Usually around 10% of women don’t marry in the MWEMP, in contrast to <3% in the HMP.

Check the footnotes in Ch 4 in my book An Empirical Introduction to Youth. The causal effect of age on pregnancy after 15 is not substantiated by the literature.

https://youtu.be/qkgU6Mhmifo?si=eOeuu8IIlq3-ZYu1

Please Aid really interesting related article by Collins giving positive reasons for women to have children at an even younger age

Here is the modern view on how it has arisen:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Western_European_marriage_pattern

See if all the reasons cited here in combination is satisfactory as an explanation.