Werner Zagrebbi has a new article out on one of my favorite topics, the origin of woke. It was reposted on Curtis Yarvin’s Substack — apparently he is Moldbug’s “old live-in intern, currently a sophomore studying computer science at a major East Coast university.” The article comments on the Rufo, Hanania, and Cofnas 'models’ of woke, and adds in the Zagrebbi model, heavily inspired by Robin Hanson and Moldbug.

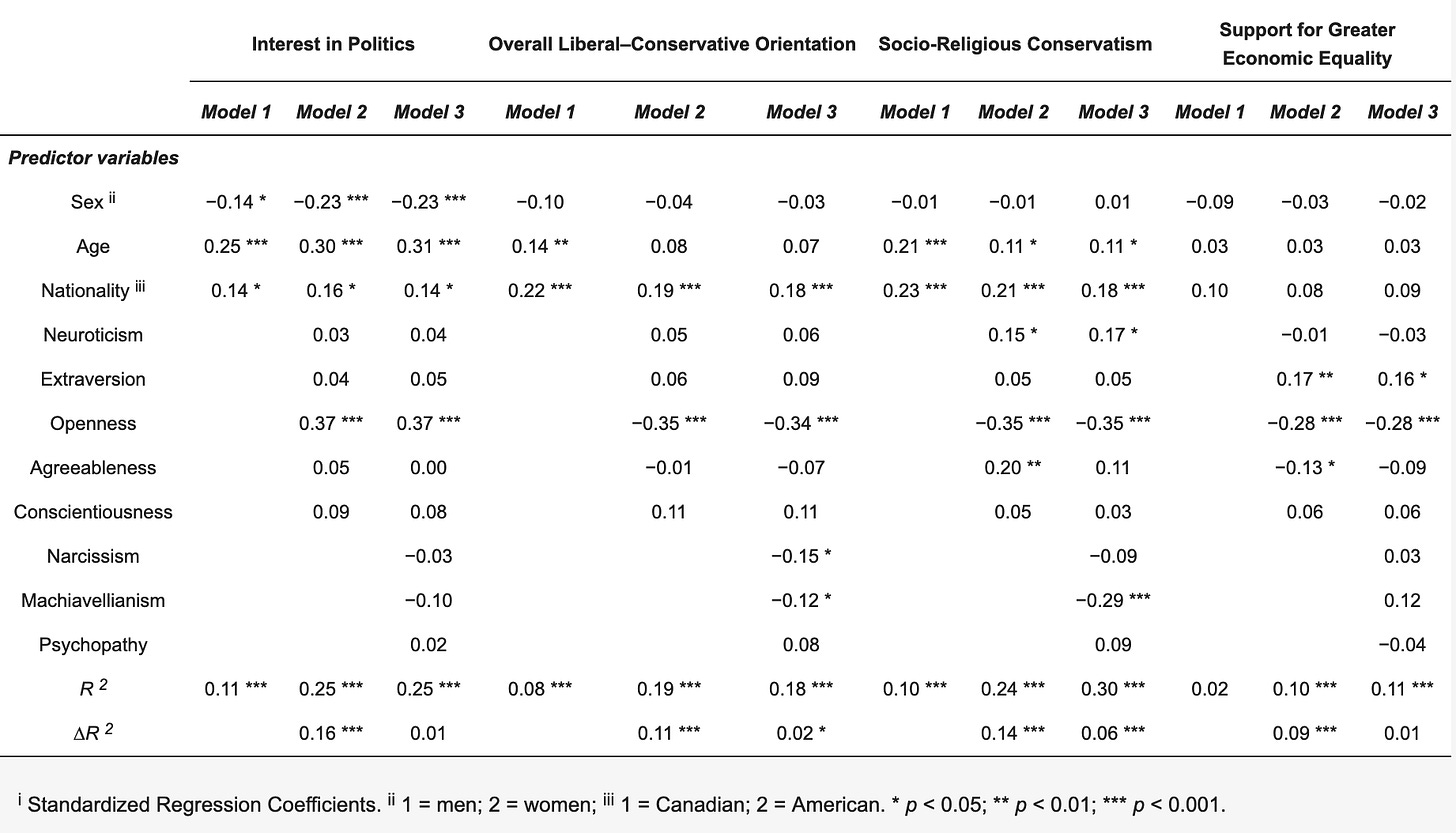

Zagrebbi’s summaries of the models are shown in the chart above, taken from his article. There are three parts of the article I would like to comment on. These are the idea that woke is virtuous, Zagrebbi’s assumptions about memetics, and the claim that hereditarianism is intrinsically taboo.

Is Woke Virtuous?

Zagrebbi writes,

Why? People who take egalitarianism seriously are more likely to behave well toward everyone, relative to nonbelievers. It’s therefore in everyone’s interests to convince others that they believe in the equality thesis.

This is a foundational assumption of his model. Without egalitarianism being a signal of good behavior, the model is totally undermined. Egalitarianism being a signal of bad behavior would mean that the signal is not adaptive, and consequencely it would never be adopted for the economic-rationalistic reasons Zagrebbi postulates — the returns to signaling would be negative.

Zagrebbi seems sure that wokeness is a sign of good behavior. He even ends his article with a call to action: “say ‘wokeness’ less and ‘virtue signaling’ more.” But wokeness is not a sign of good behavior. In fact, it’s quite the opposite.

The woke are more likely to be mentally will than the non-woke. You may be thinking, “but Bronski, the above chart shows anxiety, which doesn’t necessarily cause bad behavior.” Yes, but all mental illnesses correlate. So it isn’t surprising that being more woke also predicts being more narcissistic and Machiavellian:

I could see Zagrebbi objecting: “maybe the woke are slightly more mentally ill on average. But improved behavior toward diverse peoples far outweighs a smaller tendency towards general cluster B behavior.” But why assume diversity? Few societies in human history approached our own levels of racial diversity. Why do we have so much diversity? Not all successful societies today have as much diversity as the US — think of Russia, China, Japan — even Germany, which is over 85% white, and their right wing is discussing Abschiebung, while ours discusses unlimited H1B immigration. Not to mention plenty of other smaller European countries — Denmark, Czechia, Austria, Poland, to name a few. Some of the societies I mentioned are woke, while others are less so. Historically, the Roman Empire was quite diverse, but not so woke. Diversity doesn’t cause woke — woke causes diversity, sometimes.

The US is diverse largely because it is woke, not the other way around. Diversity proximately comes from the Hart-Celler Act, which was passed in the wake of the civil rights movement — i.e., wokeism. Zagrebbi could object and say that wokeness is specifically whatever emerged in the 2010s, so it came after diversity in the US, not before. Brushing aside how this ignores the weak global correlation between woke and diversity, I’d find this reasoning to be adhoc. Civil rights was the wokeness of its day — Zagrebbi’s mentor Moldbug is known for saying “cthulu swims left”. Wokeness is the newest left. Civil rights was never before seen leftism, and it emerged without diversity. If woke and civil rights come from the same process, then diversity is not a necesarry part of the continuation of that process.

If a model of woke should explain civil rights too, then Zagrebbi’s model fails. Even if not, Zagrebbi’s reasoning is weakened by the correlation between wokeness and mental illness.

Memetics

Zagrebbi writes,

We TESCREALists1 believe in Yarvin’s memetic evolution, and that wokeness has picked up nifty mind-virus (if that isn’t too negatively connotated) adaptations that make it especially communicable.

I have not publicized enough that I’ve developed a new mathematical model of memetics. It is, to my knowledge, the first one that features parameters that are able to be estimated with data. There are not many competing models — only a few from the 1980s that never went anywhere, because they can’t be verified or falsified with data. My key equation looks like this:

You can read it here. Now what does it mean? Delta_M is the change in the average memotype over a generation. This gives our model’s first postulate:

Human behavior is affected by a large sum of memes, similar to the effect of genes.

This means each meme has an average effect on human behavior. The average memotype is the sum of the effects times the probability of each meme being in a person’s brain. This notion contains an insight that may be surprising to some people: individuals may hold many memes with opposite effects on their behavior. The memetic component of their behavior is the sum of these effects.

The older models of memetics were essentialist in that they held that there was, for example, “the cooking meme.” Individuals could only have a single “cooking meme”, and their character was identified entirely with the meme. This is similar to old Mendelian ideas about genes. It was thought that there was an “intelligence gene” that made on smart or dumb.

We now know that intelligence is highly polygenic, meaning thousands of genes contribute, and each individual has many genes which pull their intelligence below the mean, and many genes which pull their intelligence above the mean. Their intelligence genotype is the sum of all the effects of their genes. The fact that intelligence is determined by a large sum of genetic effects is why it is normally distributed.

Political phenotype is also normally distributed. It would not be if it were the result of a small set of determistic memes. Insofar as politics is determined by memes, it must be many memes that sum to produce the ultimate memotype of each individual. This should also make intuitive sense — hopefully you hold many ideas, some that bias you toward the right, and some toward the left.

Now for the second part of the model. For simplicity, we imagine a process where one generation discretely replaces the former every number of years. When this occurs, the new generation must sample the memes of the old generation. They will also produce new memes. Delta_S is the sampling effect, and Delta_N is the production effect.

If the new generation is entirely similar to the old one, then they should ultimately be expected to have the same average memotype as the old generation after sampling time. There will be a sampling error, however, but we assume it will be zero because the population is so large — this assumption comes in at the approximation signs.

If the new generation is different from the old one, then it might cause a sampling bias. This is represented with the difference Delta_G and the correlation between the difference and memotype, r_{g,m}. This leads us to the second postulate of the model:

Genetic (and exogenous environmental non-memetic) effects on behavior are prior to memetic effects.

Memes are learned, and they are learned when genes are already fully inherited. Given the generally high heritability of mental traits, it is very likely that sampling bias will be downstream of genetic changes. This will produce an memetic evolutionary amplification effect, which is similar to the social epistasis amplification posited by Woodley & Sarraf. Thus, what looks like memetic changes is really amplification operating on top of genetic evolution.

Memetic changes due to sampling bias could also, of course, be amplifications of non-memetic environmental changes. However, since humans make most of their environment, and heritability estimates for mental traits are so high, my priors are that this will mostly not be the case.

Some readers might object, “but evolution can’t be that fast!” This is not the case. Evolutionary pressures can easily be fast enough to explain observed changes in political behavior, even without memetic amplification. The notion to the contrary seems to be based on a combination of low heritability estimates and Mendelianism. When behavior is highly heritable and polygenic, small correlations between reproduction and the trait can cause relatively large changes in the genetic mean of the next generation. This is because extremely small changes in gene frequency over 20,000 genes that all contributed to IQ adds up to a large difference in the resulting weighted sum of effects over the new generation.

Next we discuss the new meme generation process. The new generation will make new memes. First we consider the case when the new generation is identical to the old one. The new memes should have the same average effect as the old ones, plus a reality bias. This reality bias represents the unfolding of truth, technological innovation, and so on.

If leftism comes from reality bias, then MLK Jr. was right when he said “the moral arc of the universe bends long, but toward justice”. In some sense, leftism coming from the reality bias would mean it is true, just, and that humans are deeply evolved to realize leftism. I assume all rightists are comfortable in assuming this is not the case, so we can ignore the intricacies of the notion of reality bias for now.

Like at sampling time, there will also be a generating time bias due to cohort differences. Not much more needs to be said on this — if the new cohort is genetically more leftist, then their meme creators may tend to produce new memes with a more leftist average effect than the memes of the previous generation. When rightists sample from these memes, they come away more leftist than if they had lived further back in time. Nonetheless, this is merely an evolutionary amplification effect, just like the one at sampling time.

We can sum this up with the third postulate of the model:

Memes are created by humans.

This is really common sense, but the Yarvin “model” doesn’t always fully subscribe to this postulate.

Assessing the mind virus view

The mind virus view can be summed up as follows:

Human behavior is detemined by a small number of super-memes.

Genetic and environmental effects are negligible, so in a sense, human behavior is entirely memetic.

Humans are created by memes. Memes are created somewhere else, such as wherever “egregores” live.

The name mind virus is fitting, because this is close to how pandemic viruses work:

The sickness is caused by a single virus.

Only virus exposure predicts sickness.

The virus came from an animal somewhere, so it evolved exogenous to human genetic and environmental pressures. Smallpox came from cows, the bubonic plague came from fleas on rats, COVID came from bats, flu comes from birds, etc.

We see this model in Zagrebbi’s article. He says, commenting on the sucess of wokeness:

Signaling high status is a good niche for a meme—the universal human desire to acquire and project the greatest measure of status might as well be the foundational “law” of status econ.

His analysis is predicated on the idea that it is important to explain the huge contagiousness of a single meme. This is downstream of the mind virus model’s first assumption. Because the memetic component of wokeness is polymemetic, this is a flawed analysis. Zagrebbi must explain the emergence and success of potentially thousands of independent memes, each which have small effects, and why exactly conservative counter-memes did not neutralize their effects with counter-effects.

Of course, he could make this work — increased diversity causes sampling and generation bias towards woke memes. But now we’re back the the first section of the article, except with a clearer view. How did diversification happen, exogenous to woke? Did it “just happen”, like solar flares or a little ice age, or did it happen because of some preceding change to human behavior? Given the diversity record of past societies, I’m thinking the latter.

Next Zagrebbi writes:

The proles don’t become woke because wokeness continuously evolves to alienate them—that is what makes the status signal accurate in the first place.

He needs to explain an observation, that there are class differences in woke, using his model. But this is very mind virus assumption 2 loaded. Zagrebbi has no evidence for a complex memetic adaption process constantly leaving proles in the dust — plus, it contradicts his general framework. Pandemics don’t just infect elites, they want to infect everyone.

It makes more sense that class political differences are related to class genetic differences. Conservatism is highly heritable, and if anything the proles are more susceptible to memes.

Taking knowledge to be a measure of crystalized IQ, and elites to be high IQ, we can estimate that wokeness is 74% heritable in elites and 31% heritable in the proles. One reason for this may be that smarter people sample more memes, leading to lower variance due to sample size. Would heavier sampling lead to a more woke mean? Only if the number of memes sampled makes the memetic component more dominant (but then it would contribute more to variance despite there being lower sampling variance…), or if smarter people sample more woke memes on average. But if smarter people sampled woker memes, why are smarter memes woker? People generated the memes, so we conclude that smarter people are woker.

I believe they are woker because of genetically mediated population stratification. Specifically, the elite are more genetically woke because of differences in selection pressures relative to the proles. This is what makes woke high status, not the opposite. Woke is not intrinsically high status in the egregore cave, leading to adoption by the elite — woke is high status because the elite created it, because the elite are instrinsically woker than the proles. This follows more or less from postulate 3.

I conclude that Zagrebbi’s model is flawed. Now we can reflect on why. My model is based on data and mathematical logic. Zagrebbi’s model is based on blog posts — particularly those of Moldbug, Scott Alexander, Robin Hanson, and Richard Hanania. Obviously, a model based on data and mathematics is more likely to be true than one based on popular blog posts.

This is true for three reasons:

Popular blog posts can’t use math because math is hard, and the blog posts have to be popular. Therefore, they can’t use logic at a high level, because logic at a high level is just math written in English.

Instead of high level logic, they have to appeal to the audience’s accepted heuristics. These heuristics will be both simplistic and biased.

Popular blog posts are limited in the amount of data they can use — it can’t be complex or offensive to the audience. They will also not tend to use more data than what they need in order to attain popularity, even it is simple and not offensive. An entertaining story will be more popular than a lengthy literature review.

What of hereditarianism?

Hereditarianism at its best is the opposite of a popular blog post. It is based on mathematics, thereby disregarding conventional behavioral heuristics, and is backed up with loads of frequently complex and offensive data.

On the unpopularity of hereditarianism Zagrebbi says the following:

This model may as well be “standing Cofnas on his head.”

…

Though Cofnas’ articles are but a few months old as of writing, his drive and that of others prove the reality of racial differences animates the projects of Aporia and their sort, who have made it their chimeric empirical quest to demonstrate the genetic provenance of The Fundamental Constant of Sociology to an jury that would sooner reject science itself. I wish them luck, but I doubt that, on the margin, writing another killer paper that moves the—regrettably—hypothetical race and IQ controversy Rootclaim a fraction of a percent closer to one hundred will have an impact on the broader culture on any reasonable time scale.

Zagrebbi intuits that hereditarianism is a nonstarter for a popular blog post. He emphasizes offensiveness. Elsewhere he writes:

As a proud person of TESCREAL, I couldn’t help but notice Cofnas’s model conflicts with one of the stylized facts of our traditional ways of sociology: that people generally form their beliefs not from an analytical weighing of relevant issues but based on what will help them as social creatures. I won't defend this with serious social science here because, one, I am a high theorist and it wouldn't help me as a social creature, and two, Robin Hanson and Kevin Simler do that in their magisterial 2017 classic, The Elephant in the Brain.

He sure talks about status a lot. I think someone is trying to craft a popular blog post. But isn’t the post offensive? It goes against woke. The book he cites is The Elephant in the Brain, a work in evopsych that claims we are all self deluding animals mindlessly following our instincts. His mentor Curtis Yarvin hates democracy!

Zagrebbi is posting to a sphere that is as offensive as hereditarianism, but isn’t quite hereditarianism. What makes it not hereditarianism? The lack of math and data. I’ve read Yarvin, I’ve read Hanson, I read The Elephant in the Brain — there’s no data in Yarvin, none on Hanson’s blog that I’ve seen, and there’s no mathematics in the book. What of the data cited?

The Elephant in the Brain is definitely telling a story. It’s also citing something, but that thing is an easily understandable mid 20th century psychology experiment. Replication crisis fans will immediately recognize that this study is at huge risk of being p hacked and that experimental psychology is generally epistemically inferior to statistical psychometrics2 . Indeed, the study’s replication record is mixed at best. I remember hearing about this next to the Stanford Prison Experiment, the authority electroshock experiment, the Asch Line Test, and the brain developing until 25 in high school psychology — all of these are taught because they are simple and attention grabbing, and all of them have failed to replicate and were originally based on shoddy experiments or even outright fabrications.

Whether or not the split brain patient study replicates, I am not comfortable with generalizing a qualitative finding in brain damaged patients to healthy people. The whole book is written like this. While it may be an exciting story, it doesn’t have the rigor I want from science.

Do those two sets of percentages (9% vs. 29% and 11% vs. 37%) look fairly similar to you? It’s almost as if they are both from a normal distribution with close to a one standard deviation different in average IQ scores, what the sage known as La Griffe du Lion dubbed the Fundamental Constant of Sociology.

The Fundamental Constant of Sociology is an elegantly simple concept. But can you imagine trying to get a Biden-Harris Administration official to understand it?

Is it simple enough though? It’s simple as far as hereditarianism goes, but have you noticed that NRx software engineers are willing to accept offensive ideas, but not math in their blog posts? What do you think international relations majors would think about Gaussian distributions and quantitative genetics?

And sure, you can always project math onto English space, but then it competes in English space with exciting stories, and the math is not exciting and it loses all of its logical power when it has to assume the form of a shadow on the wall of Plato’s cave.

I suspect hereditarianism being offensive is only half of why it gets outcompeted by other less true, but more exciting stories. What is important is that hereditarianism is also too complex.

Grok says this is yet another name for “rationalist.”

Contrary to folk intuitions, I should add! I routinely hear laymen claim that “it’s only science when it is experimental.”

See, this is the thing I don't necessarily understand about individuals that lean heavily into biology as a means to speak on issues that are both axiological and ethical in nature (in addition to other disciplines, but those are two of the larger ones), much of it comes off more as a smear than an earnest attempt to fixate on the points from a perspective that fleshes out both of those disciplines in a manner that is consonant (meaning, people are discussing the subject in equal topical terms). As one example is concerned and one you use here, let's say that "woke-ism" was even more predictive for mental illness than it is as you show (to steel man your point further), what does this mean for the truth value of their points (if we want to assume truth aptness for even a moment)? Even putting forth all the lack of context that exists within mental illness, why it's formed, and its ethical/axiological implications considering its genesis (which, again, I am going out on a limb to hand this to you), what if these individuals have proper viewpoints and are also concomitantly true about what they are saying? Wouldn't it be more pathetic for those without those mental illnesses to be that wrong according to that conditional? Many people who utilize mental illness as some sort of means to discourage some form of belief will rely on unexplained premises that stem from associations between mental illness and a lack of diligence to discern truth (the binary opposition being the narrative of the mentally-lucid intellectual (or something of higher intelligence)), things we might have been socialized to posit in to some degree through society, but either way, I feel this deserves more discussion. Maybe that explains you, maybe it doesn't, I cannot say for certain, but the point there is to acknowledge the possibility of unexplained premises wherever they *might* exist.

Perhaps I am missing the boat here, maybe you have more articles diving into the disciplines I mentioned above, and if so, I'd love to read them (you write a lot, so it's easy for something to pass through the sieve so to say). However, it does make me question on why a litany of posts you spend your time speaking on are directed towards an evolutionary perspective if that were the case, surely we would want to fixate on the thing that is more damning due to its topical consonance, right?

Great article and math. What white country has the highest asabiyyah? Hungary, Russia, Poland?